Why the Golden Age of Illustration happened?

Let’s talk about the printing methods that made the Golden Age of Illustration possible, as well as how mass literacy took place in Europe and in The United States of America.

This is the second text in the series about the Golden Age of Illustration, a period that occurred between 1890 and 1930. In our first text, we gave a general overview of what this period was, so we could understand it as a whole.

But from now on, we’re going to dive deep into each detail of its 50-year span—a period that was crucial for children's books to become an established niche.

The Golden Age of Illustration began due to three main factors: mass education, new ways of printing illustrations in books, and a rising demand for books and magazines. So, in today’s text, we’re going to delve deeper into each of these three topics, starting with the first.

The rise of mass literacy

Today, it’s nearly unthinkable that children wouldn't attend school. But this idea—that children must go to school—is actually quite recent in the grand scope of human history.

Before 1500, only a small percentage of the population was literate, mainly nobles (especially men) and clergy. The rest of the population was more focused on manual labor and religious faith.

Starting around 1500, with Gutenberg’s press, it became possible to print books more quickly, allowing more people to buy them. The machine helped lower the cost of books and sped up production. Still, books remained relatively inaccessible to most people, who couldn’t afford them and often couldn’t read.

What led to mass literacy?

Between 1500 and 1800, people’s views on literacy began to change. First, it’s important to note that being "literate" back then didn’t necessarily mean being able to read and write. For some governments, just being able to sign your name was enough to be considered literate.

Many people could read but not write. Others could read but not understand what they were reading.

Protestant-majority countries (or should I say kingdoms?) valued and encouraged literacy much more than Catholic ones. In Catholic areas, the Church didn’t promote reading and writing because followers were expected to obey its teachings rather than read and interpret the Bible themselves.

A key point about Protestant influence is that many Protestants came from the bourgeoisie. They had enough financial resources to educate their children at home.

Alongside Protestantism came the Enlightenment (1700–1789), which believed reason, science, and knowledge were the best paths to improve society and free people from ignorance, fanaticism, and oppression.

These two factors—Protestantism and the Enlightenment—combined with Gutenberg’s printing press, led financially capable European families between 1500 and 1800 to teach their children to read and write.

But there was another complication: unlike today, countries back then didn’t have unified national languages. There were more kingdoms, and each had its own dialect. For example, Italy was only unified in 1871; before that, each region had its own dialect.

In 1790, for instance, even in France—where French was the official language—only 3 million out of 28 million people spoke “proper” French. Six million didn’t understand it at all, and another 6 million could understand but not speak it correctly. Other languages were also spoken in France, such as Flemish, Basque, and German.

From 1800 onwards (or a few decades earlier in some cases), laws were introduced to make school attendance mandatory for children, kickstarting mass literacy. Here’s when those laws were introduced in some European countries:

Prussia (1763) – Frederick the Great implemented a primary education system for children aged 5 to 13.

Austria (1774) – Maria Theresa of Austria signed a law mandating school attendance for children aged 6 to 12.

France (1882) – The Ferry Law made education free, secular, and compulsory for children aged 6 to 13.

England and Wales (1870–1880) – The Education Act of 1870 established a primary school system. From 1880, attendance became mandatory for children aged 5 to 10.

Italy (1877) – With the Coppino Law, primary school became mandatory for children aged 6 to 9.

These are just a few examples of European countries that made schooling mandatory. Of course, not all children went to school as soon as these laws were enacted.

At first, children in cities began attending school. Later, when schools reached rural areas, children there began attending too. Still, these dates marked the beginning of mass literacy.

And how did mass literacy happen in the U.S.?

Now let’s talk about the United States—another country outside of Europe with key illustrators during the Golden Age of Illustration. The U.S. followed similar steps to Europe, but with one big difference: when Gutenberg was inventing his press, the U.S. was still home to indigenous peoples.

From 1513, the land we now know as the U.S. began to be explored by Europeans. By 1607, it started being colonized. So, as European settlers colonized the region, they brought European influences with them. As a result, the U.S. established its public education system in 1830, marking the beginning of mass literacy there.

Now that we understand how mass literacy happened—how people learned to read and write in Europe and the U.S.—let’s explore the next factor that led to the emergence of the Golden Age of Illustration.

Printing innovations that made art accessible

We’ve already mentioned Gutenberg’s press, which made mass book production possible. Before that, books were handwritten or printed with the woodcut technique, where each page was carved into a wooden block that acted like a stamp.

From 1440 onward, Gutenberg’s press allowed pages to be assembled using movable metal type, which could be rearranged as needed. This sped up book printing.

But how were illustrations printed?

Illustrations were still made using woodcut. Below, we’ll explore woodcut and other techniques that boosted the Golden Age of Illustration.

Woodcut – from 600 A.D.

This technique was developed in China, refined in Japan, and reached Europe around 1300. It involved carving the image (or text) into a wood block. Ink was applied, and the block was pressed onto paper.

Over time, artists used harder woods like boxwood and cut them perpendicular to the grain, allowing for finer detail and more precise lines in the illustrations.

Lithography – from 1796

Unlike woodcuts, lithography (meaning 'stone writing') does not require the illustration to be carved. This technique was invented in Germany in 1796 by Alois Senefelder for printing sheet music and documents. It uses a lithographic stone (limestone) and chemicals. It is also worth noting that this technique did not arrive in the United States until 1819.

The limestone, which comes from a specific quarry in Germany, is sanded until it is very smooth. The next step is to draw on the stone with a lithographic crayon, which contains more grease. The illustration can contain shadows, filled areas, or just line art; the illustrator decides how to finish the illustration.

Once the illustration is complete, the chemical process, known as etching, begins. This involves applying a solution of gum arabic and nitric acid to the illustrated stone. This solution helps the grease in the illustration to penetrate the stone, creating an area that repels water (where there is drawing) and an area that does not (where there is no drawing).

Next, it is time to wash the drawing. To do this, apply a solvent, such as turpentine, to the stone to remove the drawing. This removes the drawing from the stone, but leaves the grease deposited on it.

Using a sponge, apply a layer of water to the stone, followed by a layer of ink using a roller. Repeat this process until there is enough ink on the stone to print the drawing. Place the paper to be printed on the stone and use a lithography press to print the drawing onto the paper. To print more copies of the same illustration, simply repeat the water and ink process, then pass the stone and paper through the press again.

Once all the necessary copies have been printed, the stone can be reused to create other illustrations. To prepare it for this, simply sand it enough to remove the grease that has penetrated.

See the entire lithography process below:

Note that limestone, as well as granulated zinc and aluminium, was used as a base for the drawing. This is because a metal matrix was used for illustrations that were on the same page as the text. Illustrations that took up an entire page used the stone as a matrix.

Chromolithography – from 1837

Though Senefelder envisioned color printing, Godefroy Engelmann patented chromolithography in France in 1837.

Chromolithography makes it possible to print colour illustrations. This technique uses one colour of ink for each stone, and when these colours are transferred to paper, they combine to create a coloured illustration. Imagine each stone as a layer of ink. Sometimes, 6 to 40 stones were used for a single illustration to achieve the desired colours.

There were even manuals showing which colours should be placed on top of each other to achieve the desired result. There were also specialists who planned which colours should be used on the stones to achieve the desired result.

The first chromolithography in the United States was produced in 1840.

Over time, improvements in the application of colours led to the development of the CMYK process, which made printing coloured illustrations much easier. This meant that fewer stones were needed, speeding up the printing process.

During my research, I came across the following video, which I would like to share here to complement the subject:

Photogravure – from 1870

Developed by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1852 and perfected by Karl Klic in 1870.

The process involved exposing a photographic positive (i.e. illustrations could only be printed if they had been photographed) to ultraviolet light while in contact with a copper plate coated with light-sensitive biochromated gelatin.

After this, the plate was washed. The UV light hardened the gelatin relief that remained on the plate. Next came the etching stage, in which the plate was submerged in ferric acid. This passed through the gelatin and corroded the copper to different depths depending on how hardened the gelatin was.

Finally, ink was applied to the plate and deposited in the grooves created by the corrosion. Thus, the image was transferred to the paper.

Halftone – from 1881

In 1881, Meisenbach patented a printing process known as halftone. First studied in 1852, it became the dominant method for reproducing images in newspapers and books from 1890 onwards, due to its affordability and high-quality results.

This process is important for printing because it enables smooth gradients to be created in illustrations. Thus, instead of only blocked shadows, there was now variation in tone.

This was achieved by converting the image into a pattern of dots of varying size and density. The converted image was engraved onto a metal plate and used as a matrix for printing the illustration.

Initially, illustrations were photographed and then converted into a dot pattern. Over the years, however, illustrators began drawing their illustrations directly in dots, as can be seen in the example below:

Offset Lithography (CMYK) – from 1904

Offset lithography is an evolution of lithography. Now, a metal plate onto which the illustration had been transferred is attached to a machine consisting of several rollers. Some of these rollers were for ink, for the paper that would receive the print, for water, and for attaching the metal plate.

Additionally, only four colours were needed to print any coloured illustration. This reduced printing time and costs.

A new demand for illustrated books and magazines

The combination of mass literacy and new printing techniques meant that books became objects of desire for the middle classes, who had access to literacy. Reading became a popular leisure activity, particularly among wealthier families.

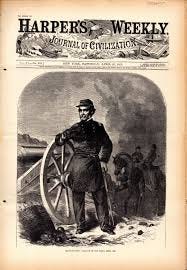

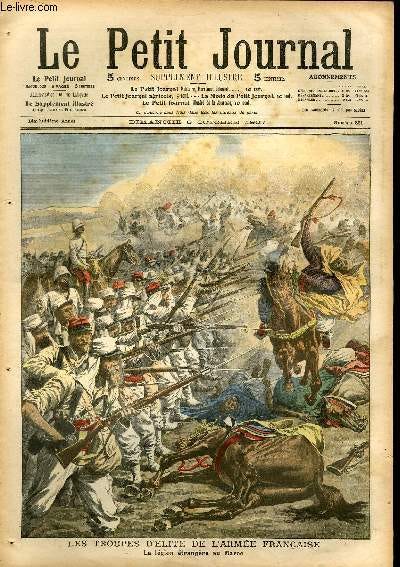

Additionally, illustrators began to be regarded more as artists than craftsmen. Weekly and monthly magazines for adults now featured illustrations, as was the case with:

Harper’s Weekly

The Saturday Evening Post

Scribner’s Magazine

Le Petit Journal illustré

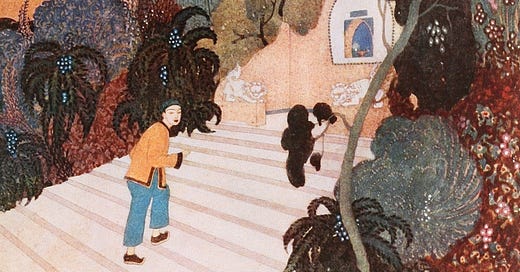

Publishers also began investing in illustrated children's books. This gave rise to the market for aesthetically pleasing literary gifts—books not only with text, but with beautiful, colorful artwork by renowned artists. These served both as gifts and as tools to encourage children's literacy.

This was the Golden Age of Illustration, a time when illustrators were celebrated and in demand to enrich books and magazines. It left a lasting influence on the children’s illustration market.

I hope, despite the long read, that you’ve learned a lot about how this period came to be. If you have questions or thoughts, feel free to leave a comment below.

See you next week when I’ll write about the pioneers of the Golden Age of Illustration.