Howard Pyle and the birth of modern illustration in America

The story of the father of American illustration and his legacy for an entire generation of illustrators.

Among the many artists of the Golden Age of Illustration, a few stood out more than others. Howard Pyle was one of them—it is no wonder he is considered the father of American illustration.

He was an immensely important artist for an entire new generation of illustrators. Moreover, he was one of the pioneers of the illustration profession as we know it today. Not to mention, of course, that he played a crucial role in the Golden Age of Illustration: thanks to the books he wrote and illustrated, children’s literature rose to prominence in the United States at the time.

Who was Howard Pyle before becoming a famous illustrator?

Howard Pyle was born in 1853 in Wilmington, Delaware, USA. From a young age, he showed an interest in drawing, and, encouraged by his parents, he studied for three years in the studio of Francis Van Der Wielen, a Belgian artist who had opened an art school in Philadelphia. Later on, he also took classes at the Art Students League in New York.

This was essentially the extent of his formal art education. After all, his parents owned a leather goods store and did not have sufficient financial means to send him to an art school in Europe (something that was common among those whose parents were well-off).

However, he studied on his own, and did so diligently. He learned by studying paintings, observing, and constantly practicing drawing. In 1876, he traveled to Europe to see the works of the old masters up close.

He moved to New York for a period to be closer to magazine publishers and thus obtain illustration work. After some time trying without much success, he finally landed a major opportunity: illustrating two pages for Harper’s Weekly magazine. Over time, he became one of the most successful artists of his era. After four years living in New York, he returned to Wilmington.

Howard Pyle’s artistic vision

Pyle’s inspirations for his illustrations came from various sources, such as Romanticism, and also from contemporary artists like Walter Crane.

In his illustrations, the central elements were:

1. Narrative and Historical Authenticity

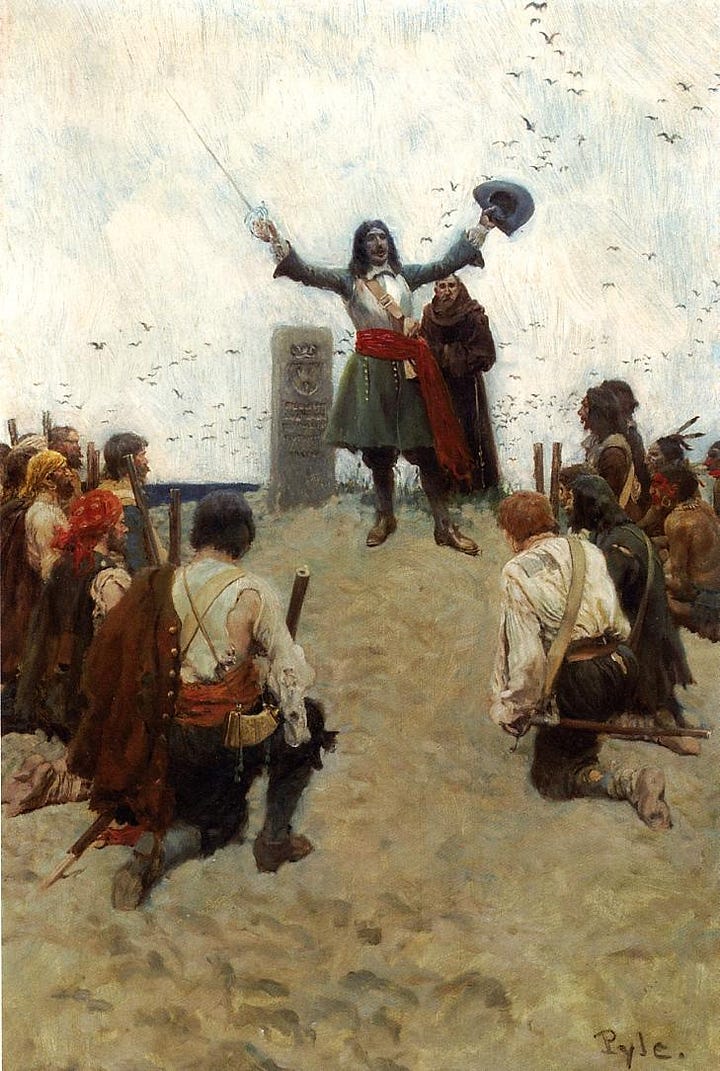

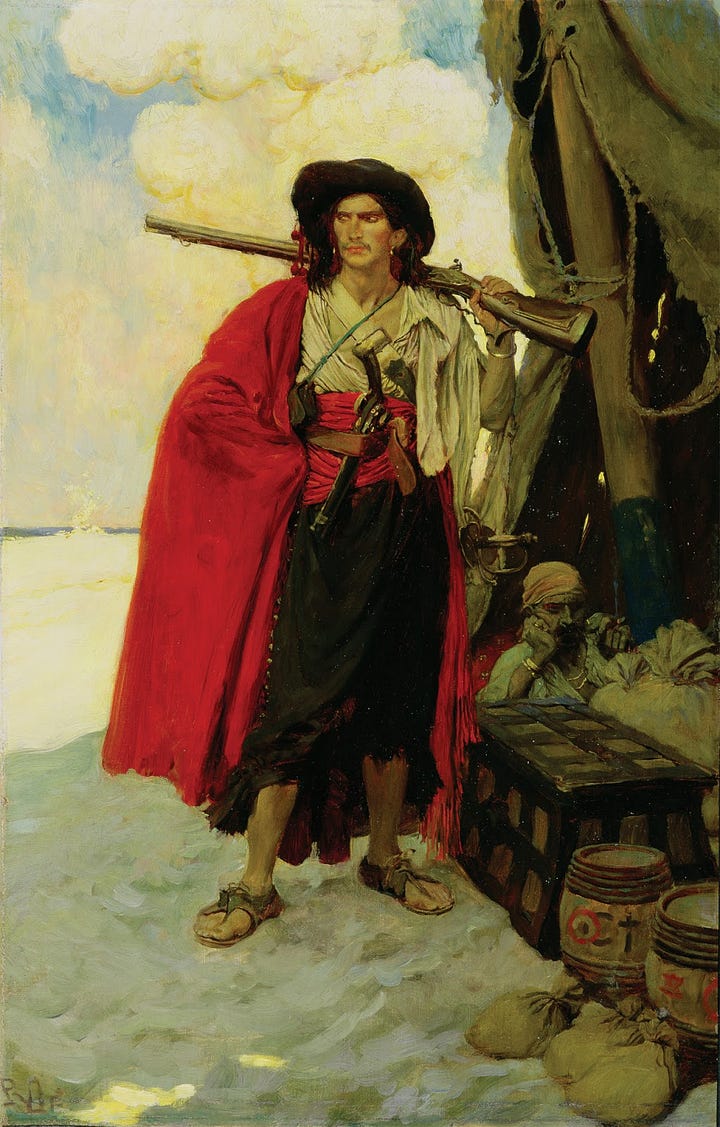

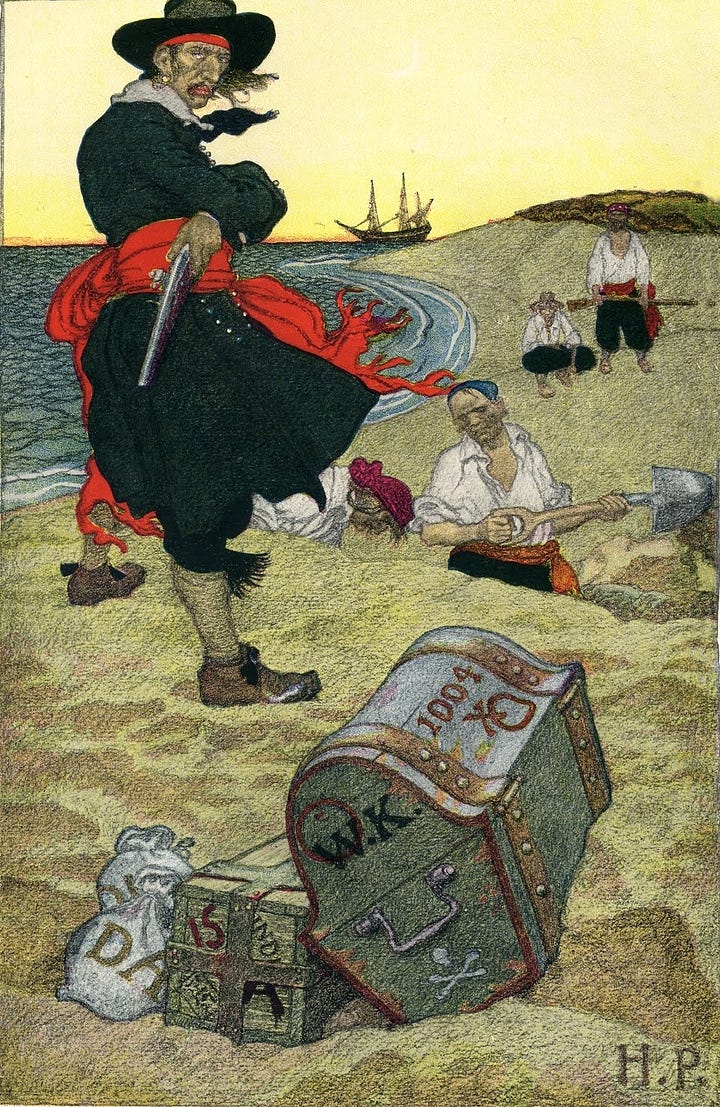

To create his illustrations, he conducted research on the objects and clothing of the period he was depicting, and if any information was missing, he would fill in the gaps with his imagination. This is the case, for example, with the pirates’ clothing in his Book of Pirates. At the time, there were few details about how pirate clothes should look, which led him to create the concept of pirate dress we still have today.

The scenes he chose to illustrate in his books often portrayed moments of drama. Even in crowded scenes, every figure was present for a reason. Additionally, his characters were placed in dynamic poses, so you could often see what their next movement would be, giving the drawing more fluidity.

In this way, he managed to tell a story through the elements within the illustration, whether through the characters’ expressions and poses that hinted at action or hidden thoughts, or through other elements we will look at next.

2. Dramatic Composition, Color, and Light

The composition of his illustrations was always designed to tell a story. There was always a focal point, and he created depth by overlapping figures, along with including a background.

The use of light was essential in his illustrations—it helped narrate the story within the image and was also a key component in the composition itself. Howard Pyle was inspired by the way Rembrandt and other old masters used light, employing bold contrasts between light and dark.

Regarding color, when you look at Pyle’s colored illustrations, he often worked in earthy browns, reds, and ochres, lending warmth and a sense of authenticity. If you observe them closely, you’ll notice that the color red—so visually commanding—was added in strategic places to guide the viewer’s eye.

3. Artistic Materials

Pyle typically worked in:

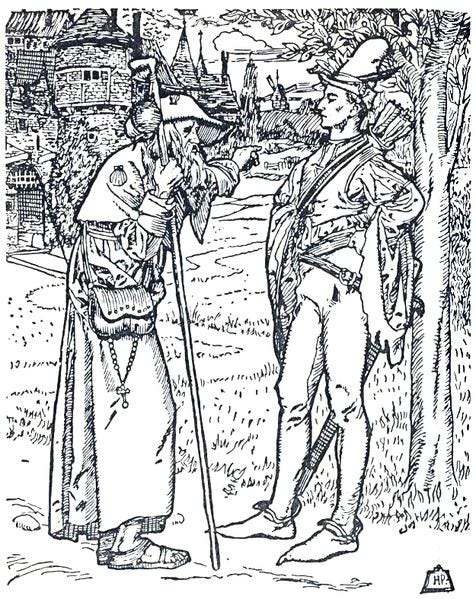

Pen and ink: for sharp, detailed line work, especially in magazine illustration.

Oil painting: for richer color plates and stand-alone works.

Watercolor washes: sometimes combined with ink for softer effects.

According to the Art Center of Information website, these are some of the concepts Pyle believed in:

Concentrating solely on copying could stifle the imagination.

Too much emphasis on technique would result in a kind of overindulgence in which the means became more important than the message.

Creating a great many thumbnail sketches before settling on the final design. He sometimes made as many as 50 for a single painting.

The fewer the tones, the simpler the picture.

An artist should lighten the light areas and darken the dark areas so that the lights and darks were distinct from each other.

Push every picture toward the extremes. A painting with a thousand birds in the air should show one or a thousand.

Teaching the next generation: The Brandywine School

After returning to Wilmington, he continued illustrating for magazines, but in addition, he wrote and illustrated his own books, such as The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883), retold existing stories with his illustrations, and collaborated on many books about American history.

Besides working as an illustrator, he also taught illustration at the Drexel Institute between 1894 and 1900. After leaving the institute, he founded his own school in Wilmington, taught summer classes in Pennsylvania, and established a studio in an abandoned mill, which became known as the Brandywine School of Art.

Howard Pyle, considered the father of American illustration, taught many students who would go on to become renowned illustrators, including Jessie Willcox Smith, N.C. Wyeth, and Maxfield Parrish—names that also define the Golden Age of Illustration.

Pyle’s fame was not limited to the United States; his work gained international recognition. Vincent van Gogh even mentioned him in a letter to his brother Theo:

“Do you know an American periodical called Harper’s Monthly Magazine? — there are marvellous sketches in it… As well as sketches of a Quaker town in the old days by Howard Pyle.

I’m full of new pleasure in things because I have fresh hope of myself being able to make something with some soul in it.”

Vicent Van Gogh

Pyle’s enduring legacy in art and literature

Pyle was a tremendously important figure in the world of children’s illustration—and even for other fields that exist today, such as graphic novel, film, and editorial illustration. He was responsible for elevating illustration to a new level and creating the model for the profession of illustrator. Through his work, illustration began to be seen as an essential part of the literary experience.

Because of Pyle’s work, Americans share a collective iconographic universe regarding themes such as Robin Hood, Pirates, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, and the Middle Ages. For example, if you ask Americans to picture what Robin Hood looks like, they will almost all imagine a character with nearly the same physical characteristics.

Thanks to his time as a teacher, Howard Pyle was also responsible for training a generation of artists who succeeded him and became leading names of their time.

“Pyle taught me to see with my imagination.” — N.C. Wyeth

Above all, he was one of the key artists who elevated children’s literature by combining stories with illustrations that conveyed action and emotion, helping to enrich and tell the books’ very narratives.

Here is a list of the main books written (or retold) and illustrated by Howard Pyle:

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883)

Otto of the Silver Hand (1888)

The Wonder Clock (1888) (written by his sister Katharine Pyle)

Pepper and Salt (1885)

Men of Iron (1891)

The Story of King Arthur and His Knights (1903)

The Story of the Champions of the Round Table (1905) – link

The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions (1907)

The Story of the Grail and the Passing of Arthur (1910)

Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates (published posthumously, 1921) – link

After 1900, Pyle became interested in painting murals. He produced several works in this form, which led him to want to deepen his understanding of the old European masters. For this reason, he moved with his family to Italy in 1910. However, due to a kidney infection, he passed away in Florence in 1911.

This is the summarized story of one of the greatest artists of the Golden Age of Illustration—who, although he spent most of his life in the United States, had his work recognized by European artists, and whose illustrations can still be found today in textbooks.

Did you know about Howard Pyle's work and history? If you could ask him one question, what would it be?